Probing AI’s limits

Arnold & Landau AI Fellow Mikhail Burtsev is exploring how machine learning models reason. The answer could make tools like ChatGPT smarter.

Chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini often seem smart. Yet on tasks that humans find easy, they can sometimes stumble in quirky ways. When it comes to spatial awareness, for instance, researchers have found these large language models can be pretty hopeless. Asked, “I’m in London and facing west. Is Edinburgh to my left or right?” GPT-4 Turbo confidently replied: “To your left, as it is located to the north of London.” Or consider: “I get out on the top floor (third floor) at street level. How many stories is the building above the ground?” Gemini 1.5 Pro answered: “Zero stories above the ground.”

This is one of the biggest mysteries facing AI researchers today. How is it that these costly, cutting-edge machine learning tools can easily write complex computer code, or predict how a protein molecule will fold, yet they struggle with puzzles that a child could answer?

What makes this question hard is that it’s not clear how AI models reason. The chatbots run on neural networks, which crudely mimic the structure of human brains. Their remarkable ability to answer questions in a human-like way depends on training them up with reams of data—books, articles and webpages. During training, chatbots make associations between words by altering the strengths or “weights” of the millions of connections between artificial neurons comprising the neural network. This is what computer scientists mean when they say that chatbots “learn”. But we still don’t know if the outputs are merely strings of words stuck together based on the chatbot’s prior associations, or if they can meaningfully be described as the products of abstract thinking.

One way to approach the problem is to ask a simple neural network questions to which answers can be either right or wrong and formulate questions in such a way as to make it impossible for it to memorise its way to answers. Dr Mikhail Burtsev, our Arnold & Landau AI Fellow, is doing exactly that. The sort of problems Burtsev poses to AI involve predicting the behaviour of cellular automata, virtual machines that follow simple mathematical rules but can nonetheless display enormously complex, yet predictable, behaviour.

A historical interlude

Cellular automata were the brainchild of the Hungarian-American mathematical genius John von Neumann. With interests that sprawled across the sciences, von Neumann made many catalytic contributions to dozens of fields during the first half of the 20th century, some of which have shaped the modern world. His work spanned logic, various fields in pure and applied mathematics, economics, theoretical biology and physics. But he is most often remembered as the originator of the von Neumann architecture, a blueprint for an electronic stored-program computer. Published in 1945, the design still underlies practically every computer in use today, from smartphone to laptop.

Von Neumann’s interest in automata was spurred by a philosophical question dating back to the 17th century. That was when Rene Descartes declared the body to be “nothing but a machine”. To which his student, the young Queen Christina of Sweden, retorted primly, “I never saw my clock making babies.” Von Neumann would prove that, in the right circumstances, a machine could do just that.

The automata in von Neumann’s proof live on an endless two-dimensional grid. Each square or “cell” can only communicate with its four contiguous neighbours and can be in one of twenty-nine different states. One state, for instance, receives inputs from three sides and transmits to the fourth. Using these building blocks, von Neumann describes a hypothetical machine that reads a set of instructions to assemble a replica of itself. The new machine is then given a copy of the assembly instructions by the old machine, enabling it to replicate in turn.

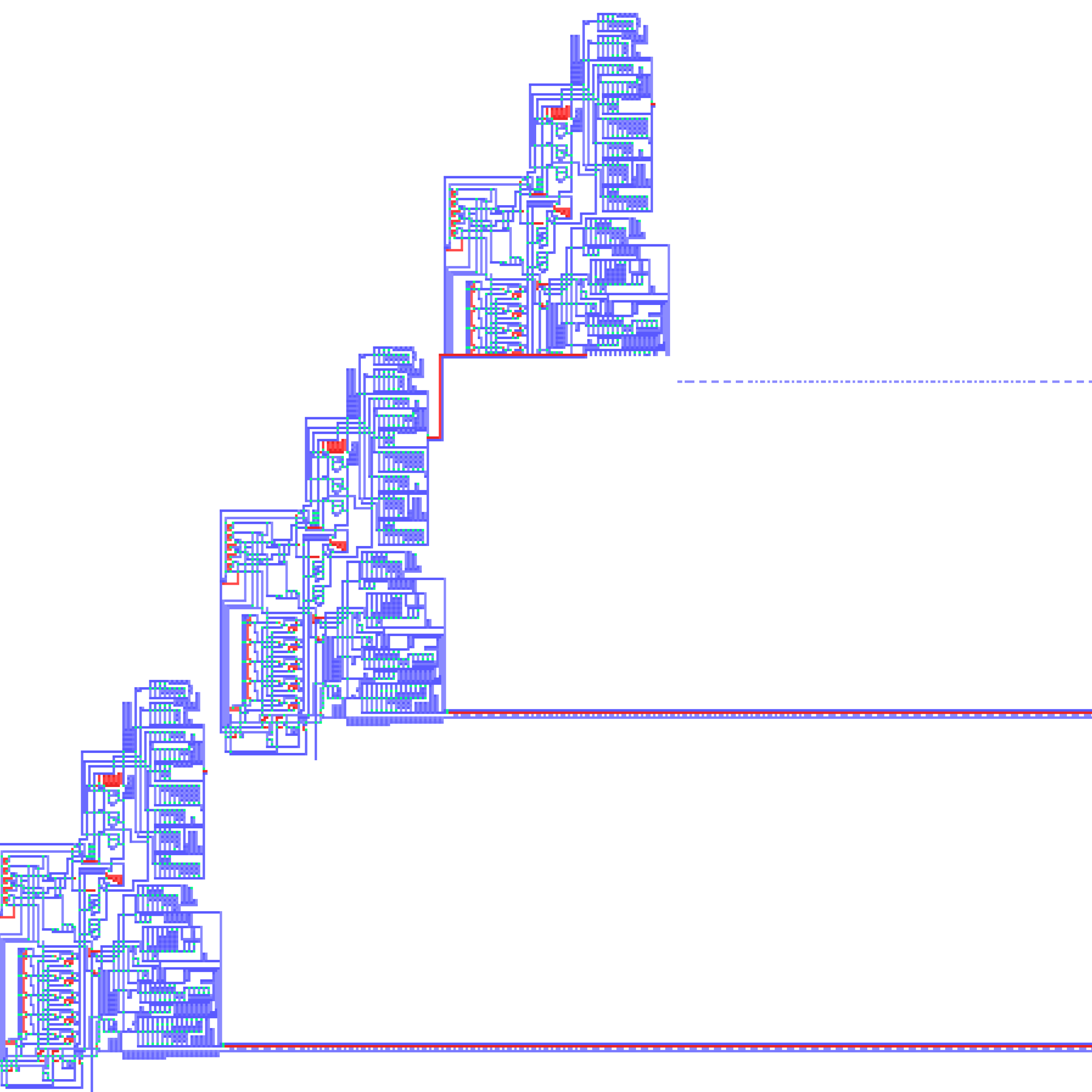

The first simulation of von Neumann’s self-reproducing automaton appeared in 1995. This screenshot of the program shows an automaton that has replicated twice. The long ‘tail’ behind each automaton is the tape of instructions it uses to reproduce. Credit: Umberto Pesavento & Renato Nobili.

In the 1980s, the physicist and entrepreneur Stephen Wolfram began playing with cellular automata, having invented them independently without knowing of von Neumann's earlier work. Unlike von Neumann’s two-dimensional designs, Wolfram’s lived on a horizontal line of cells. The state of each cell was determined by itself and its two neighbors, and the resulting state was copied to a new row of cells below, generating successive “generations” of the automaton. Because of their simplicity, Wolfram called them “elementary cellular automata”. But they were anything but.

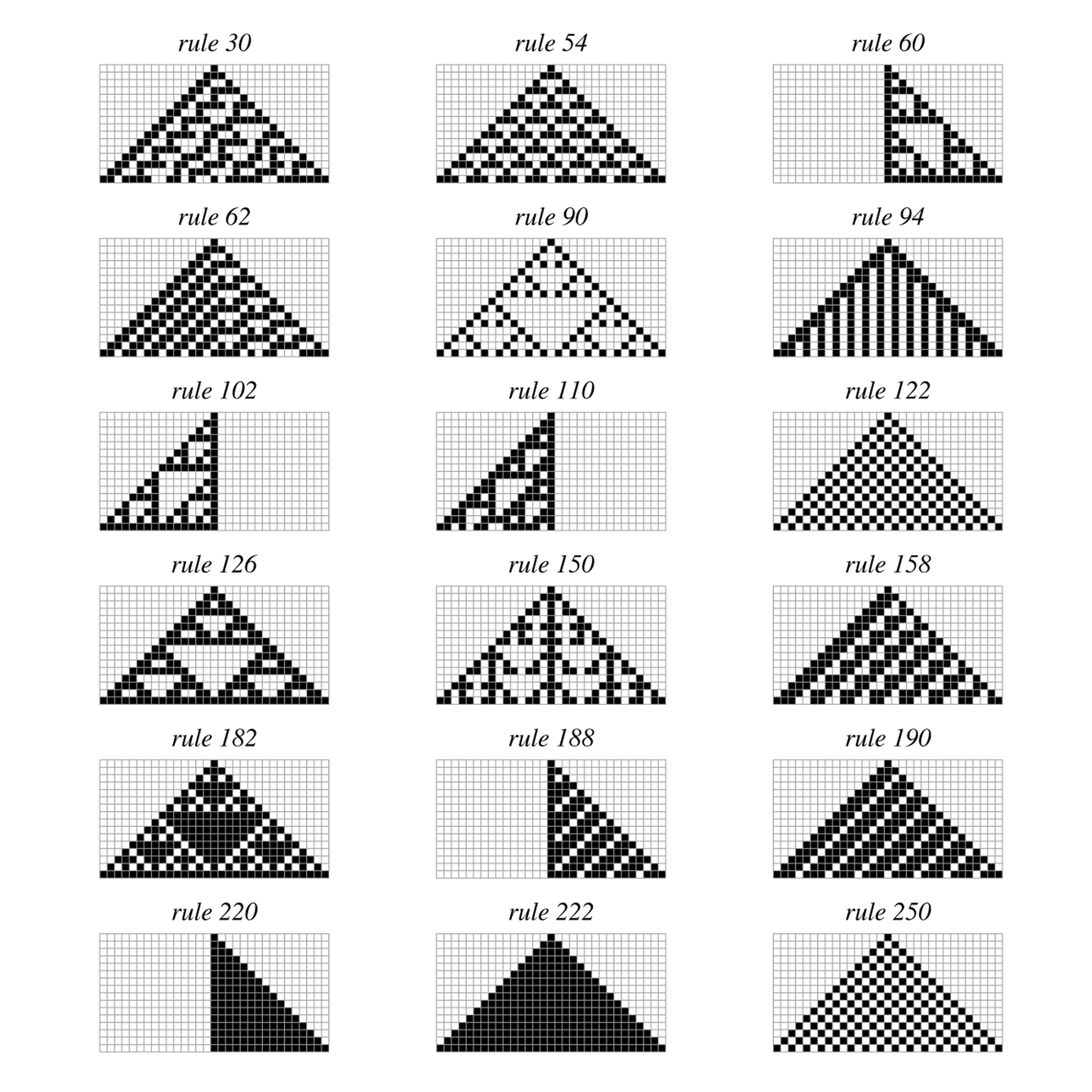

Each set of three squares can be in one of eight possible configurations. For each automaton, these configurations either result in a black (“alive”) or white (“dead”) central square on the next line, meaning that there are 2^8 = 256 sets of possible rules that totally determine the next state.

Some of the 256 elementary cellular automata.

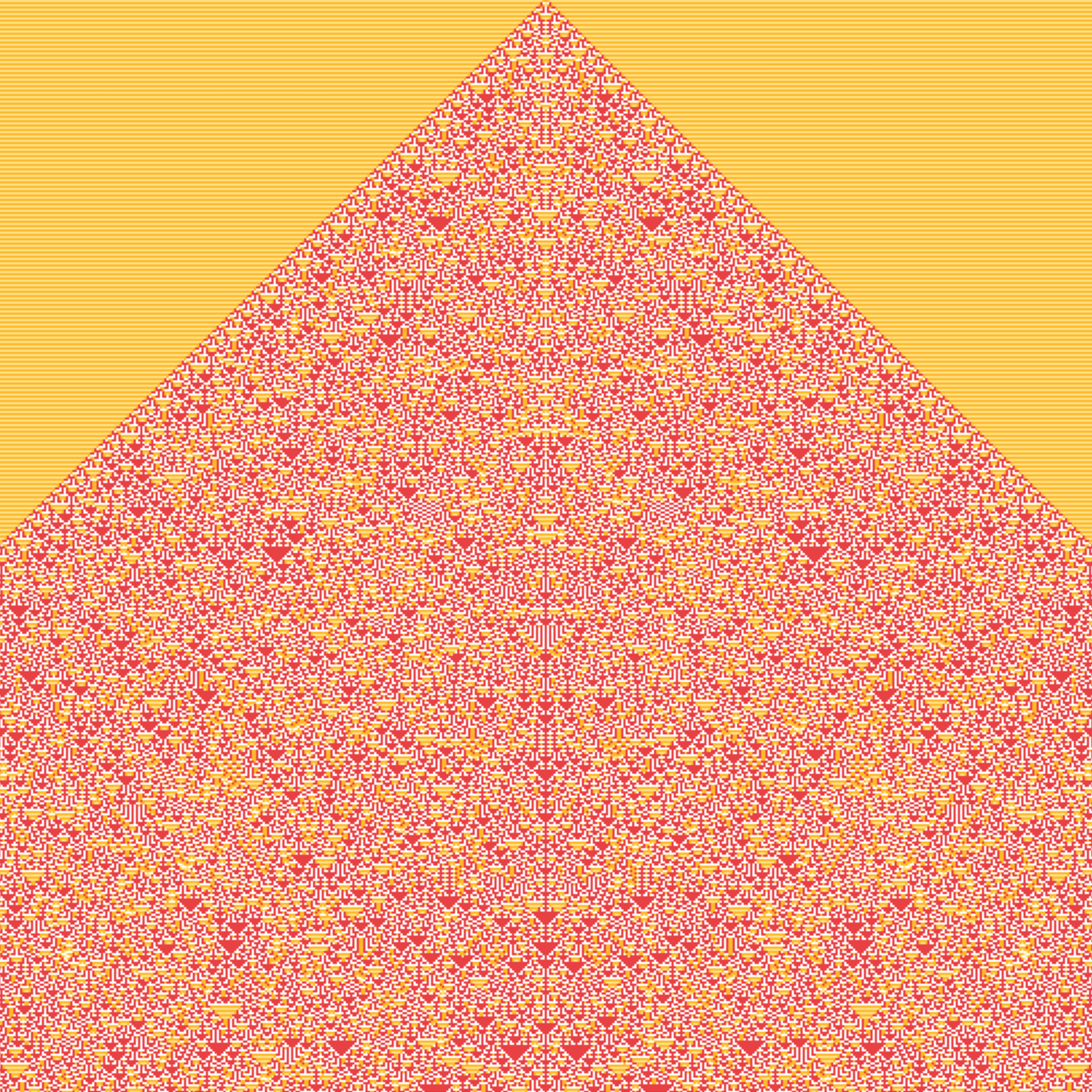

While many sets of rules result in boring behaviour—rule 0, for instance, results in a blank wall of death, whatever the starting configuration—some produce extraordinarily complex patterns. Starting from a single black square, rule 30 explodes into a froth of triangles. While each successive line is completely determined by applying the eight rules to the preceding line, whether the central column of the sequence is black or white seems to be random.

The first 15 generations of rule 30.

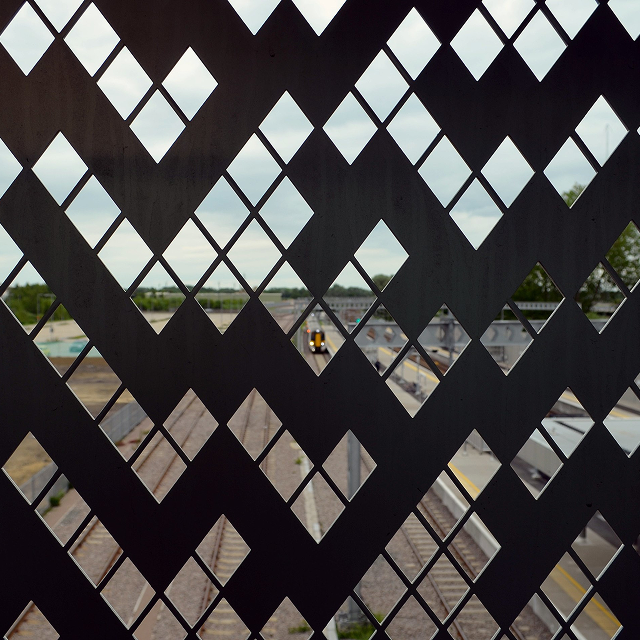

The cladding of Cambridge North railway station features parts of the rule 30 pattern.

Wolfram’s research assistant Matthew Cook went on to prove that rule 110 had even more remarkable properties. Given enough space and time and the correct inputs, rule 110 is a universal computer—able to run any conceivable programme, even Super Mario Bros.

These elementary cellular automata are the mathematical machines Dr Burtsev uses to test the reasoning abilities of AI. But rather than three-square elementary cellular automata with 256 sets of rules, he chose five-square ones. Since each set of five squares can be in one of 2^5 = 32 different configurations, there are vastly more possible sets of rules: 2^32 = 4,294,967,296 to be exact. That makes the task of predicting the evolution of these automata challenging enough to be a reasonable test of the AI’s capabilities.

Reason or recall?

Dr Burtsev generated about a million “snapshots” of different cellular automata. Each snapshot consisted of 20 lines, showing how a random initial arrangement of 20 cells evolved over 20 generations under a randomly generated rule set. He then trained transformer models on this dataset and tested them on 100,000 new automata they had never encountered before.

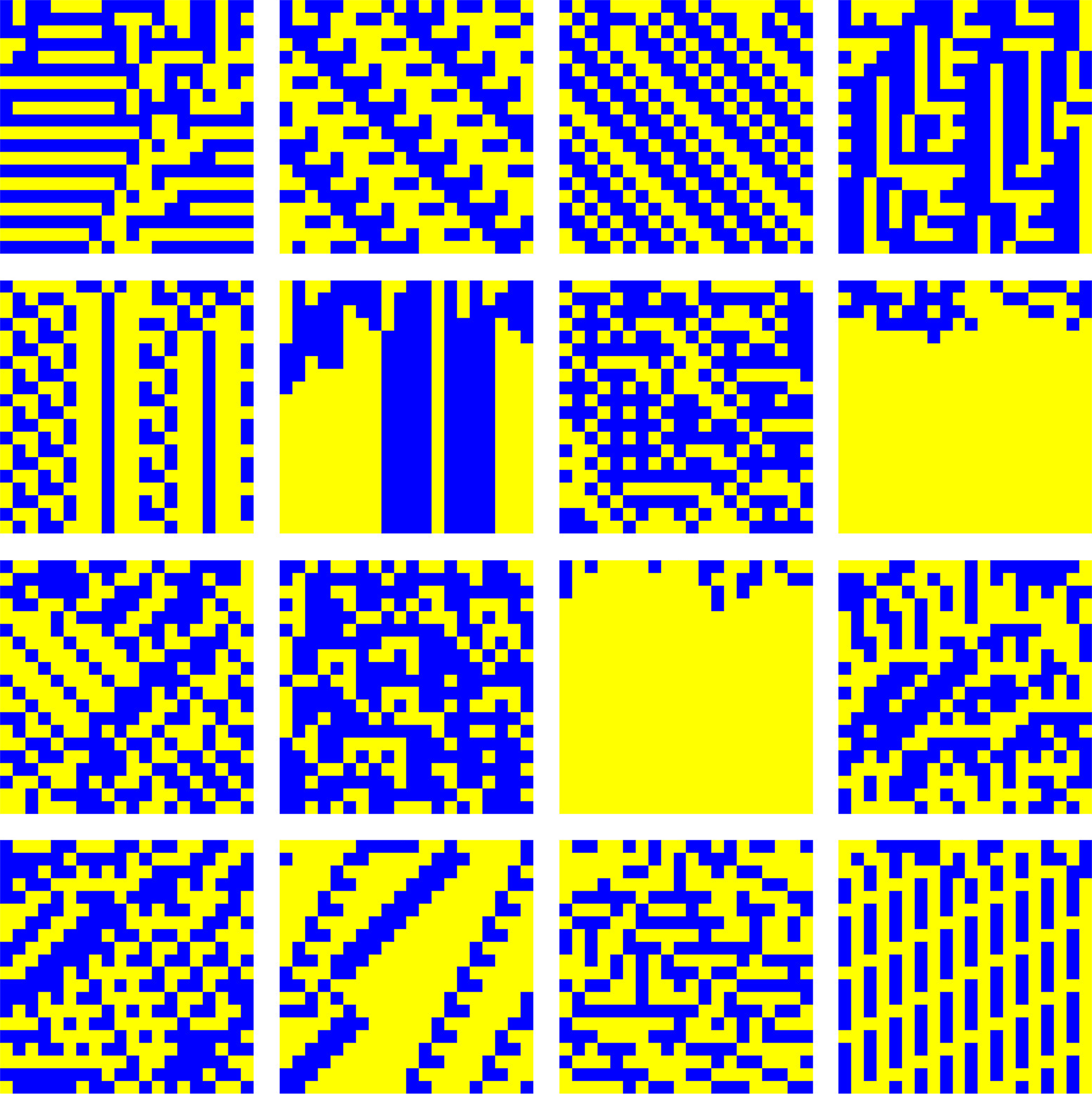

Typical grids used during training.

In his first experiment, he trained the transformer on the first ten lines of every automaton in his dataset. He found that the AI model successfully predicted the bits in the following line with 96% accuracy. Since the transformer had not been exposed to these automata before, this showed that the model was inferring the underlying rules, not merely regurgitating them.

Predicting just the next row, however, is a relatively straightforward task. For his second experiment, Dr Burtsev wanted to see whether the transformer could predict the composition of future generations without explicitly computing any intermediate ones. So once again he used the first ten lines of the automata in his dataset to train his models but asked the AI to predict the automata’s second, third or fourth subsequent generations while skipping those in between.

The model’s accuracy dipped to 40 percent for the second row and to about 20 percent for the third or fourth rows, where only trivial all “0” (all empty) or “1” (all filled) rows were predicted correctly. This raised two possibilities: the model could not deduce the rules when skipping rows, or it could not internally keep track of intermediate rows that it is not asked explicitly to predict.

To separate these explanations, Dr Burtsev gave the model the actual rule sets as part of the input. While this let the model predict the very next line accurately, performance again collapsed on longer jumps. Having established that the issue was not related to deducing the rules, Dr Burtsev considered the second possibility—that the model is failing to represent or “remember” the hidden intermediate steps.

This led to a third experiment inspired by “chain-of-thought” prompting, a technique used to improve reasoning in large language models. When trained to generate the intermediate steps explicitly rather than skipping them, the transformer’s performance improved to 95 percent accuracy on the second step—but not on subsequent steps.

Lastly, Dr Burtsev turned to the architecture underpinning the model. A transformer consists of multiple layers of neural networks, with each layer performing a specific computational task. By training models with varying numbers of layers, Dr Burtsev found that a transformer’s reasoning capacity grows with its depth: every two or three additional layers enable the model to accurately predict one more generation in the evolution of an automaton. This suggests an inherent architectural limit—a transformer’s ability to reason is bounded by network depth.

Dr Burtsev’s experiments show that transformers can indeed abstract rules and reason to a point, but their capacity to carry reasoning forward is fundamentally limited by their architecture. Without representing intermediate steps, their performance quickly breaks down. This finding helps explain why large language models improve when prompted to show their work, and why adding depth or restructuring layers enhances their reasoning abilities. Looking ahead, he suggests that more efficient designs—smaller models that use layers more effectively—could both push the limits of machine reasoning and make AI systems cheaper and more accessible, perhaps even able to run advanced reasoning tasks on everyday laptops.