Faraday’s masterclass

The Oldie, 29 Sep

In The Oldie, our writer Thomas Hodgkinson celebrates the Royal Institution’s Friday Evening Discourses, the world’s oldest science talks.

In 1852, Thomas Huxley wrote to his sister that, now for the first time, he understood “what it is to be going to be hanged”. Yet the biologist hadn’t literally been condemned to death. The reason for his sense of mortal dread was that he had just delivered a public lecture.

To be fair to Huxley, his one-hour presentation on “animal individuality” wasn’t any old lecture. It was a contribution to what remains one of the most illustrious speaking gigs in science. The Friday Evening Discourses at the Royal Institution in Mayfair, which this year celebrate their 200th birthday, are the world’s oldest ongoing series of science talks.

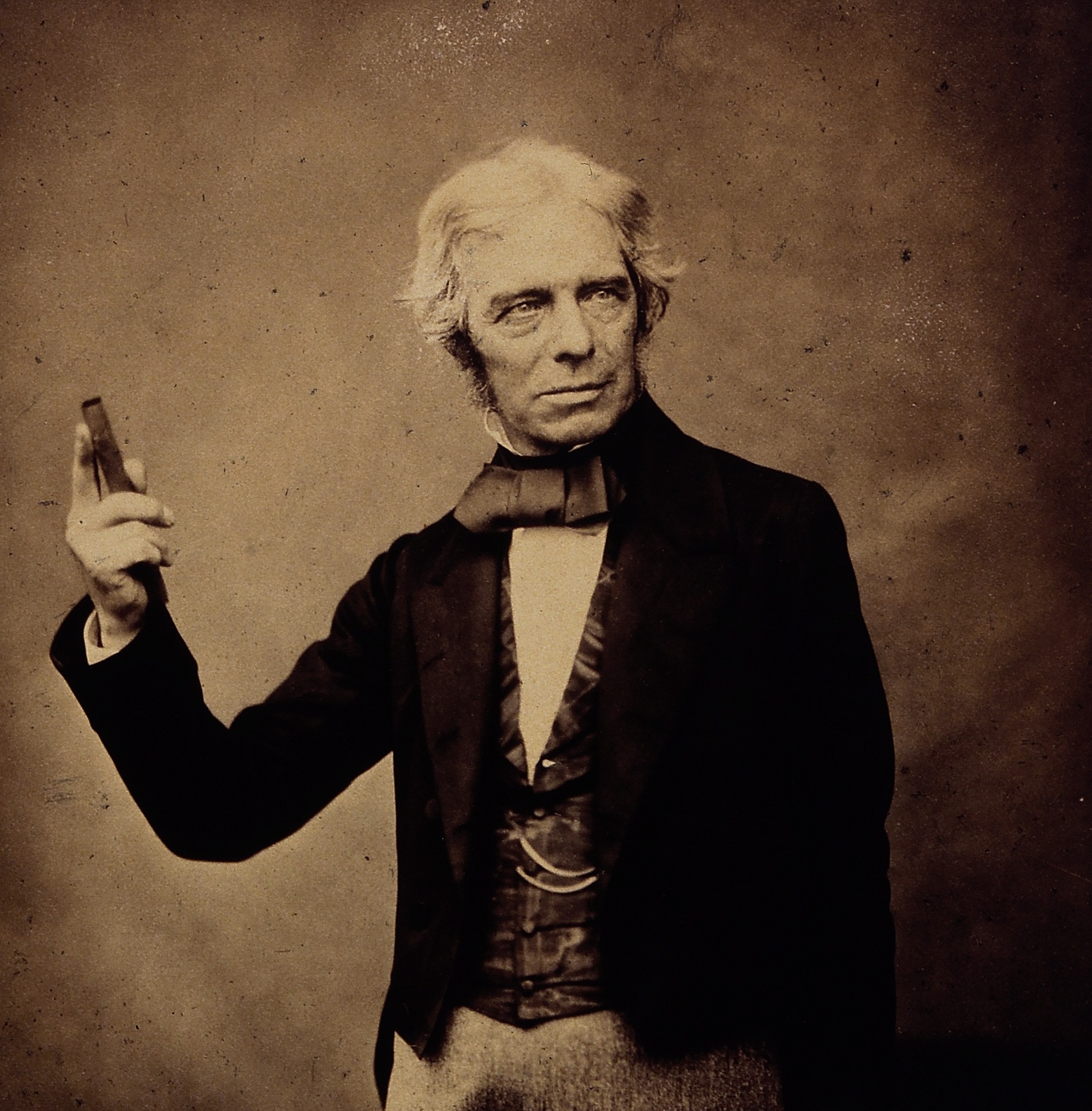

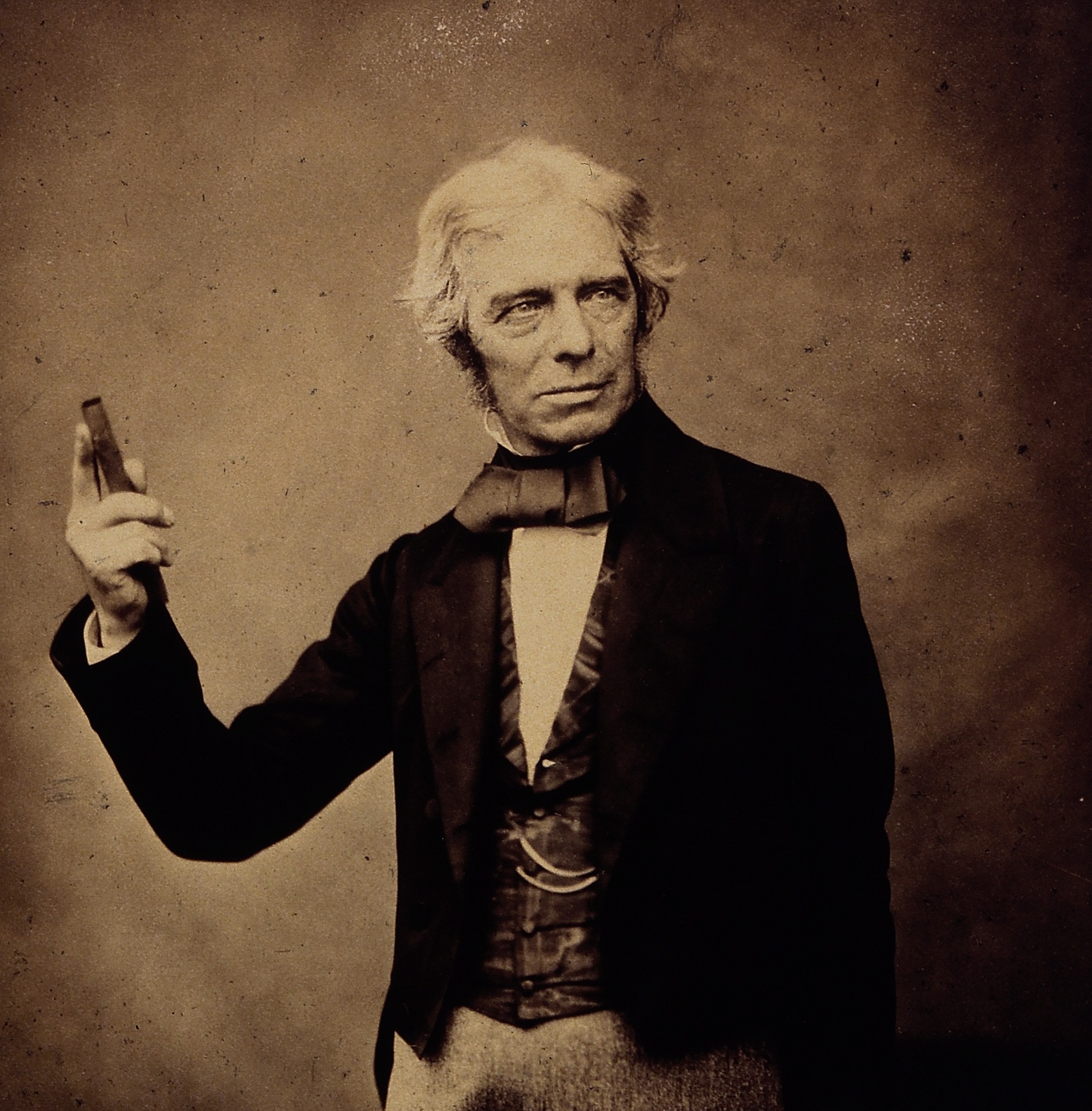

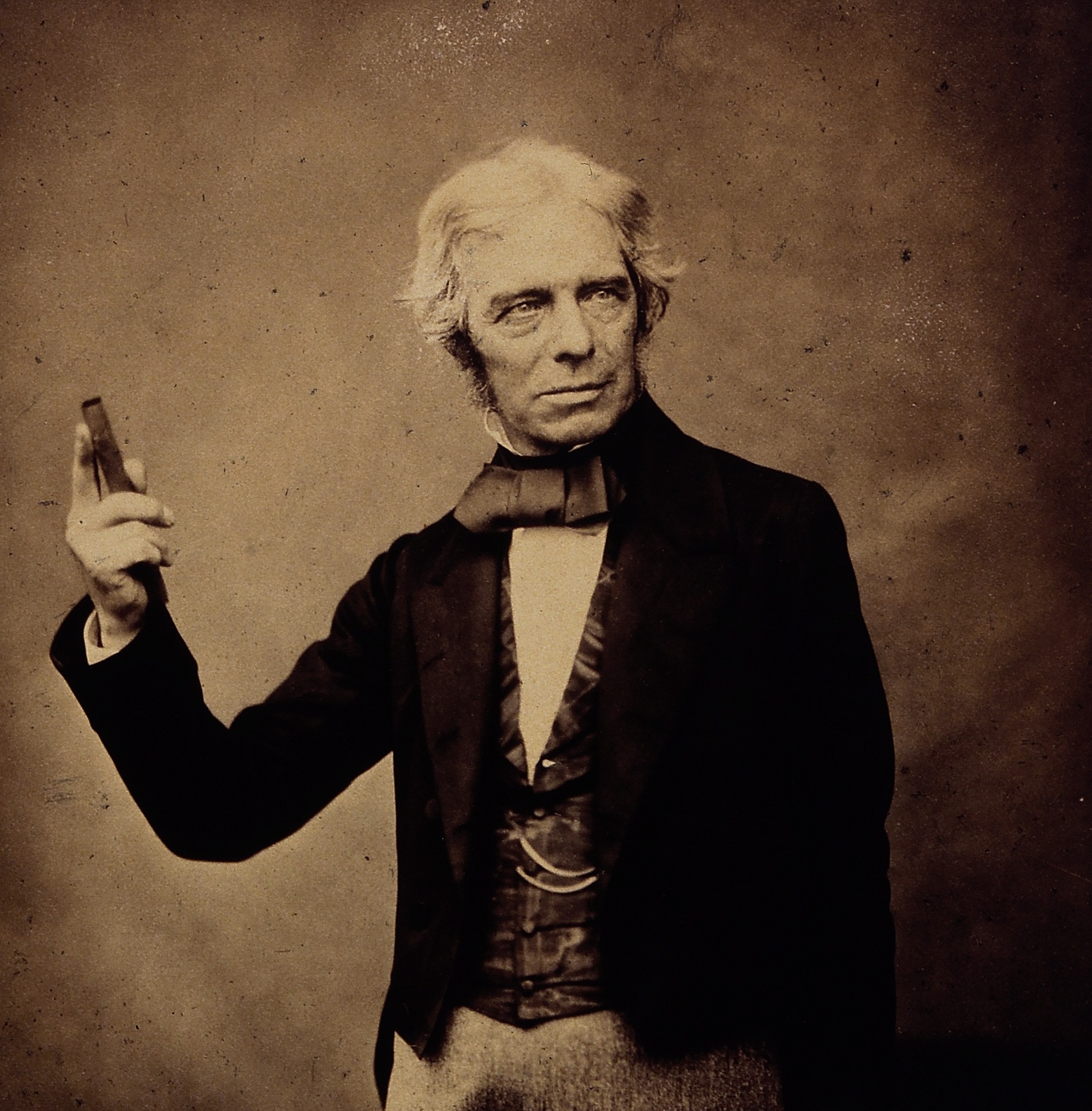

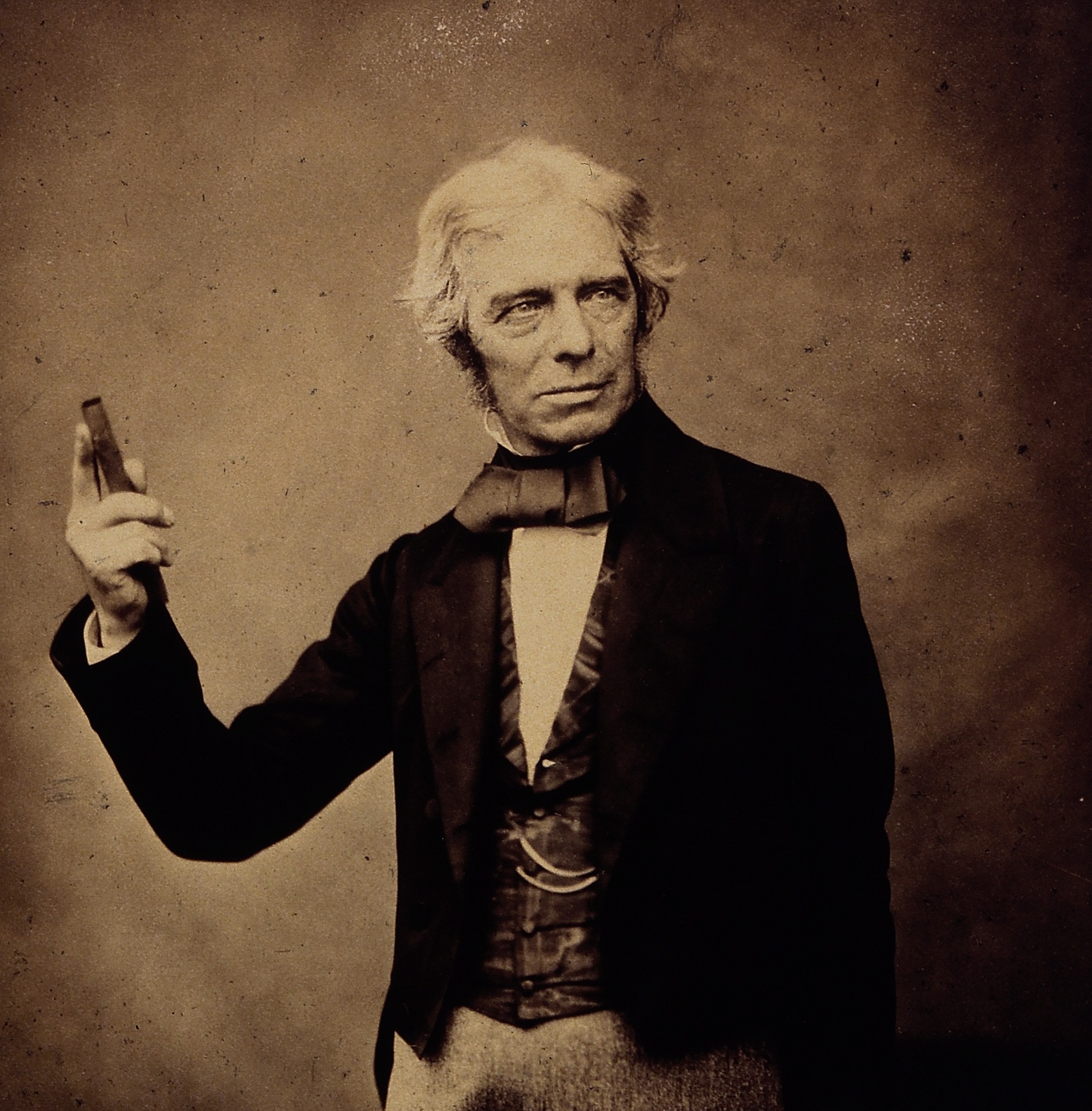

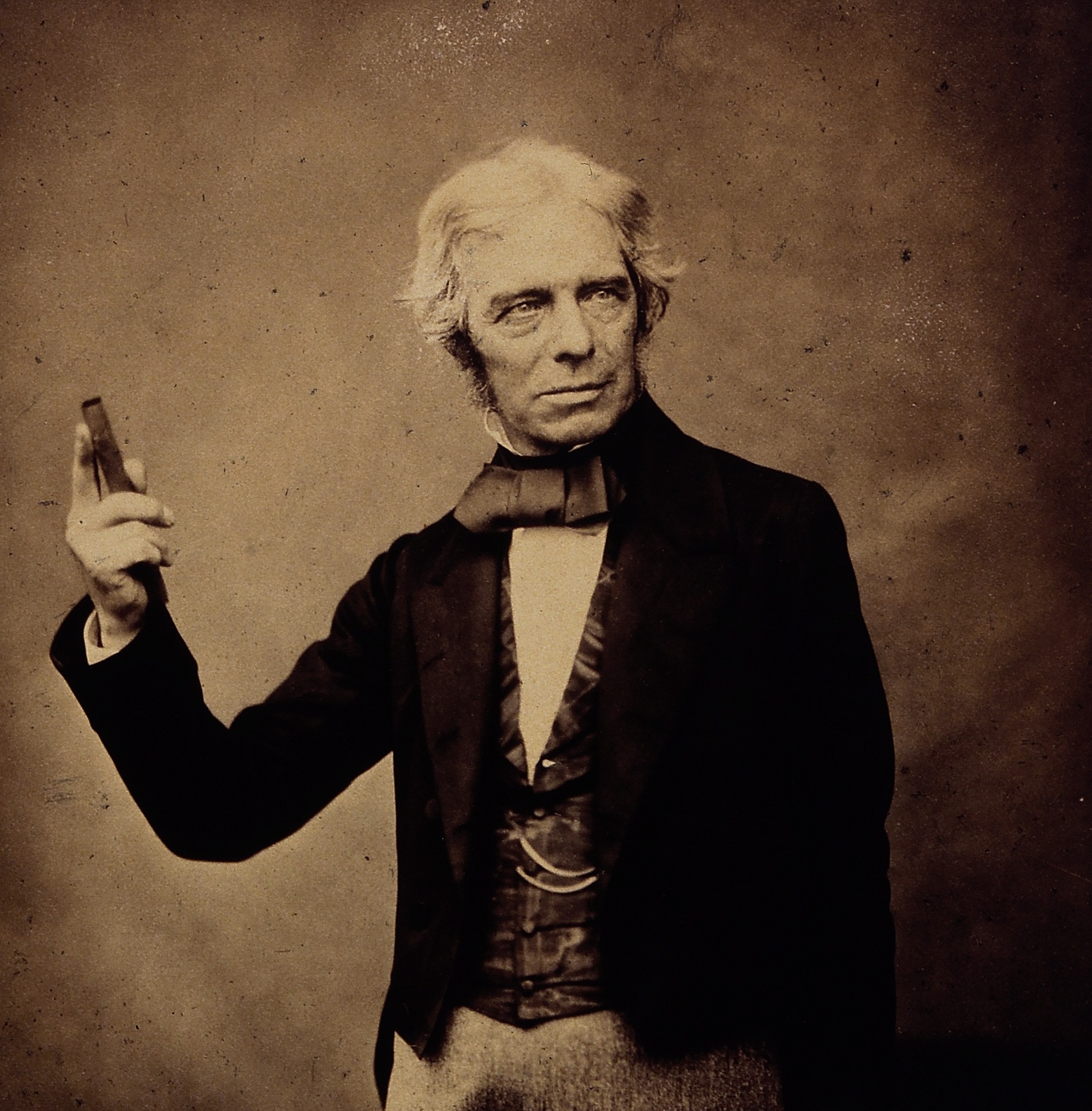

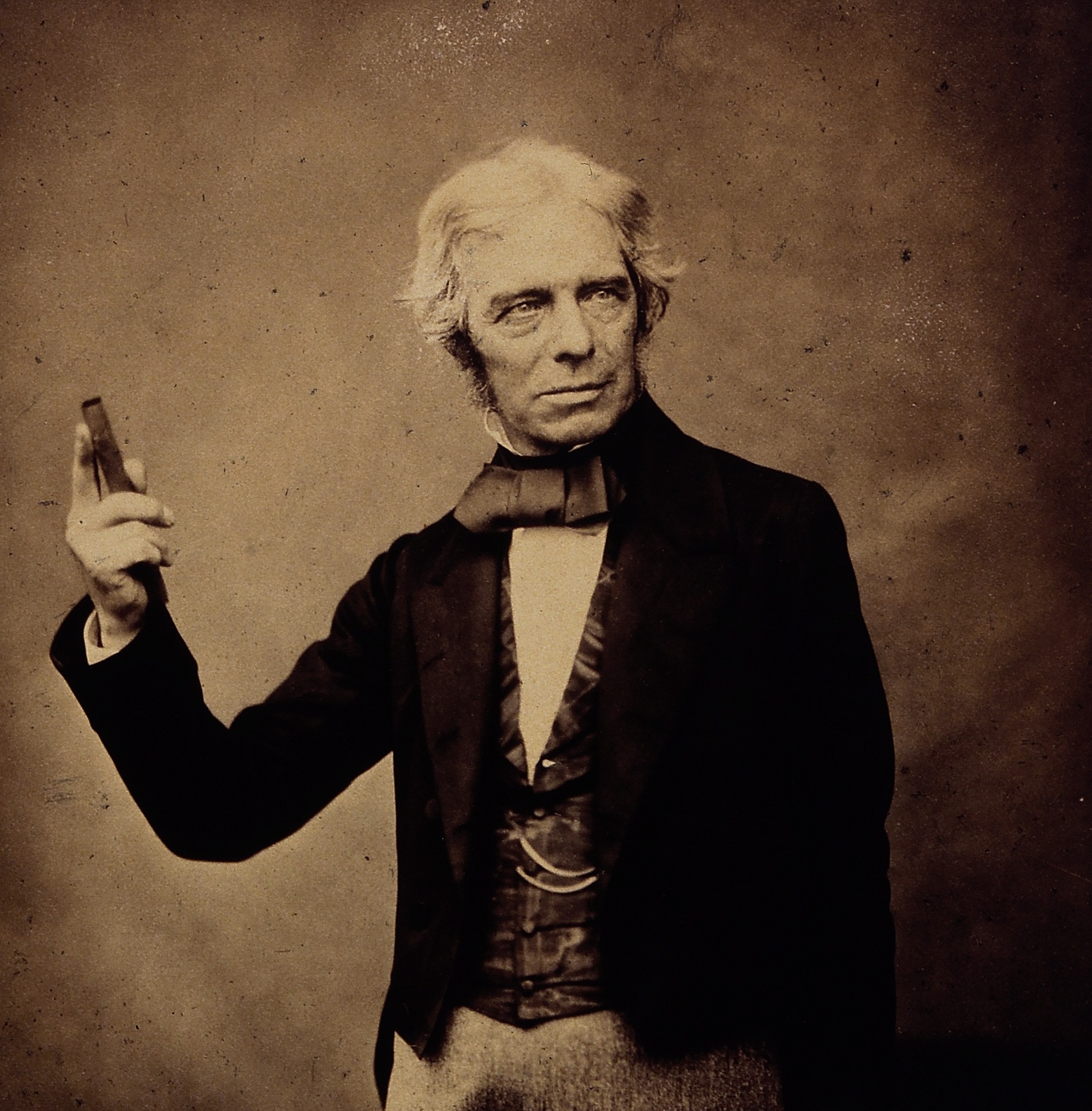

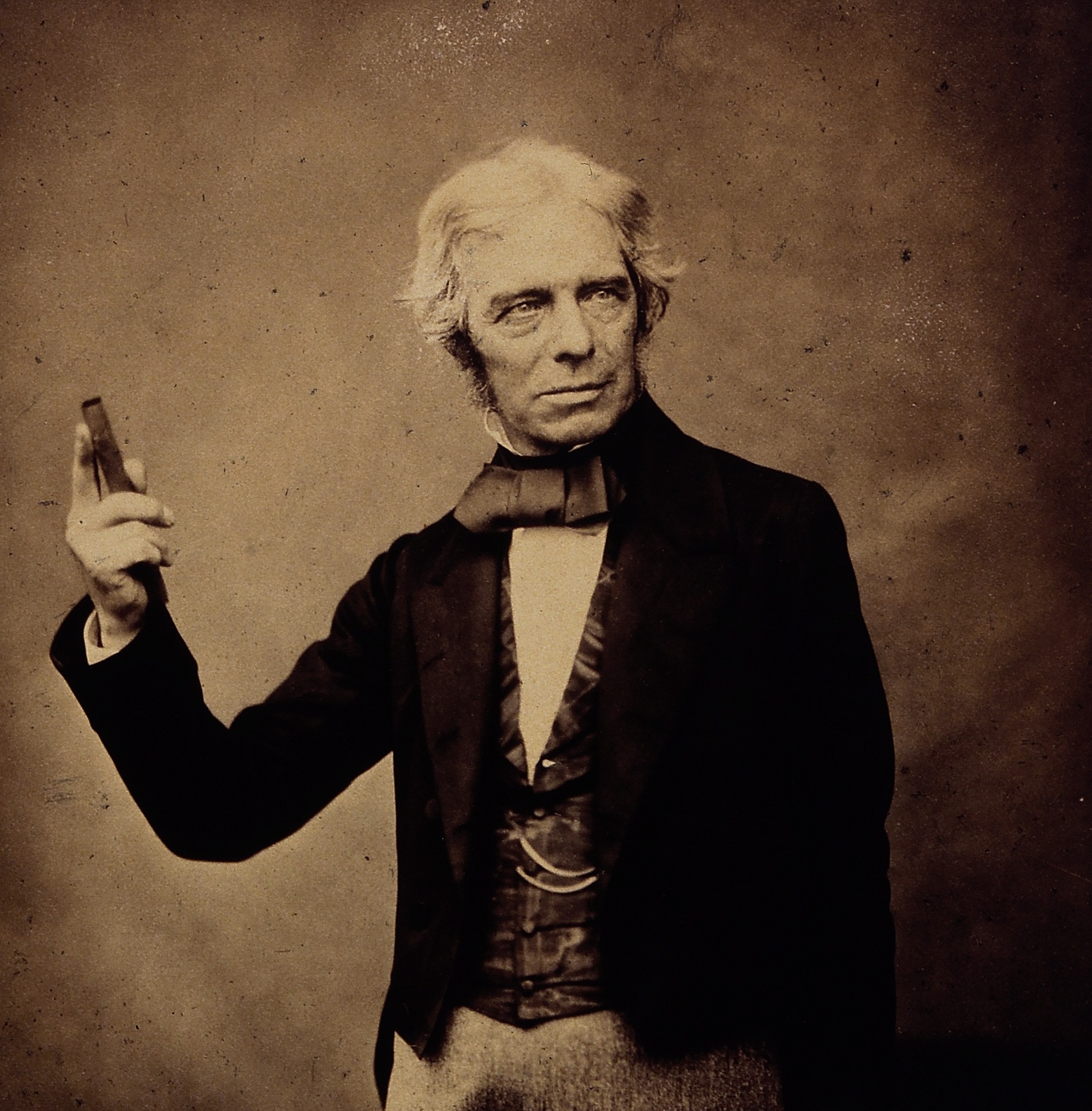

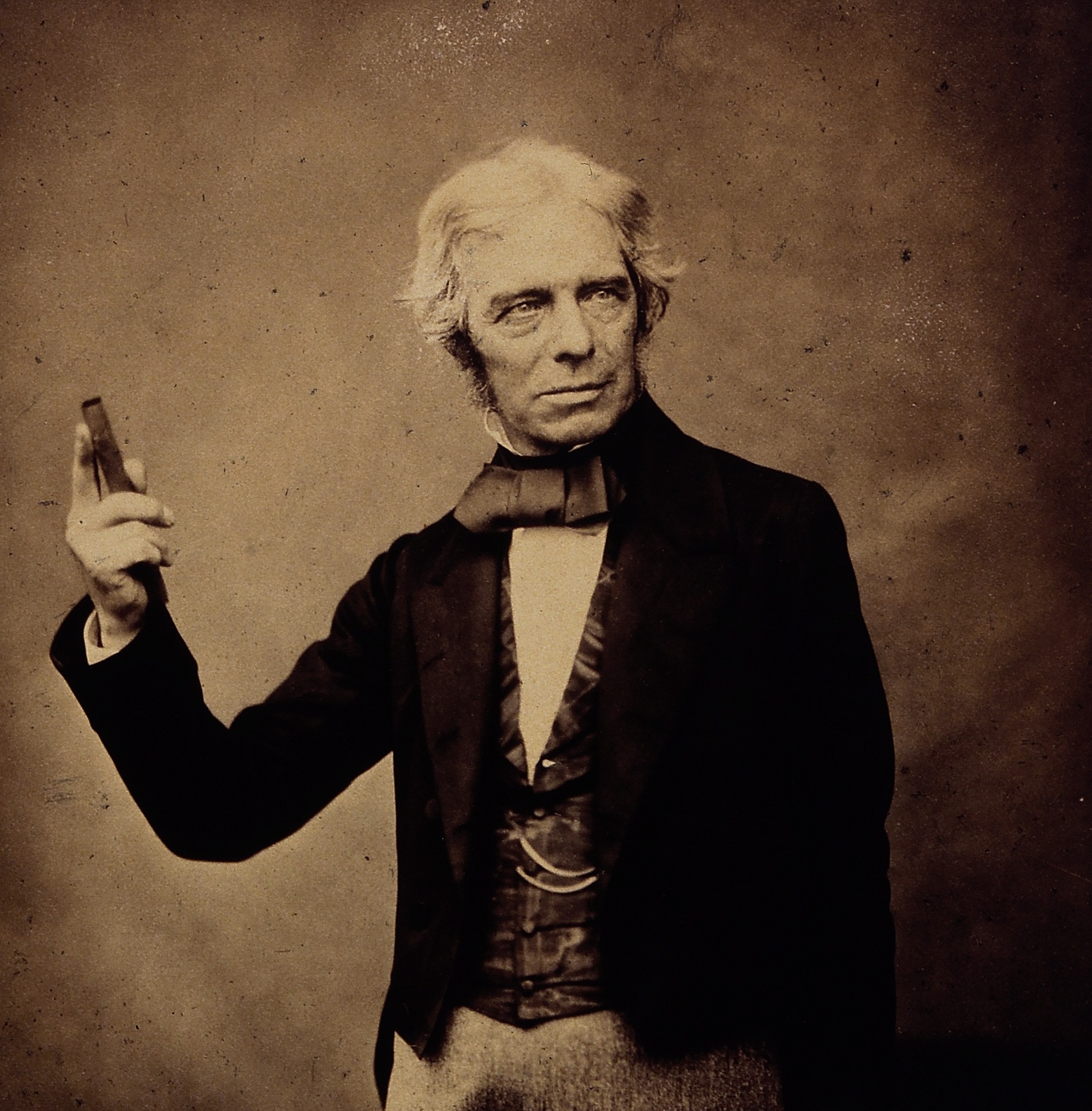

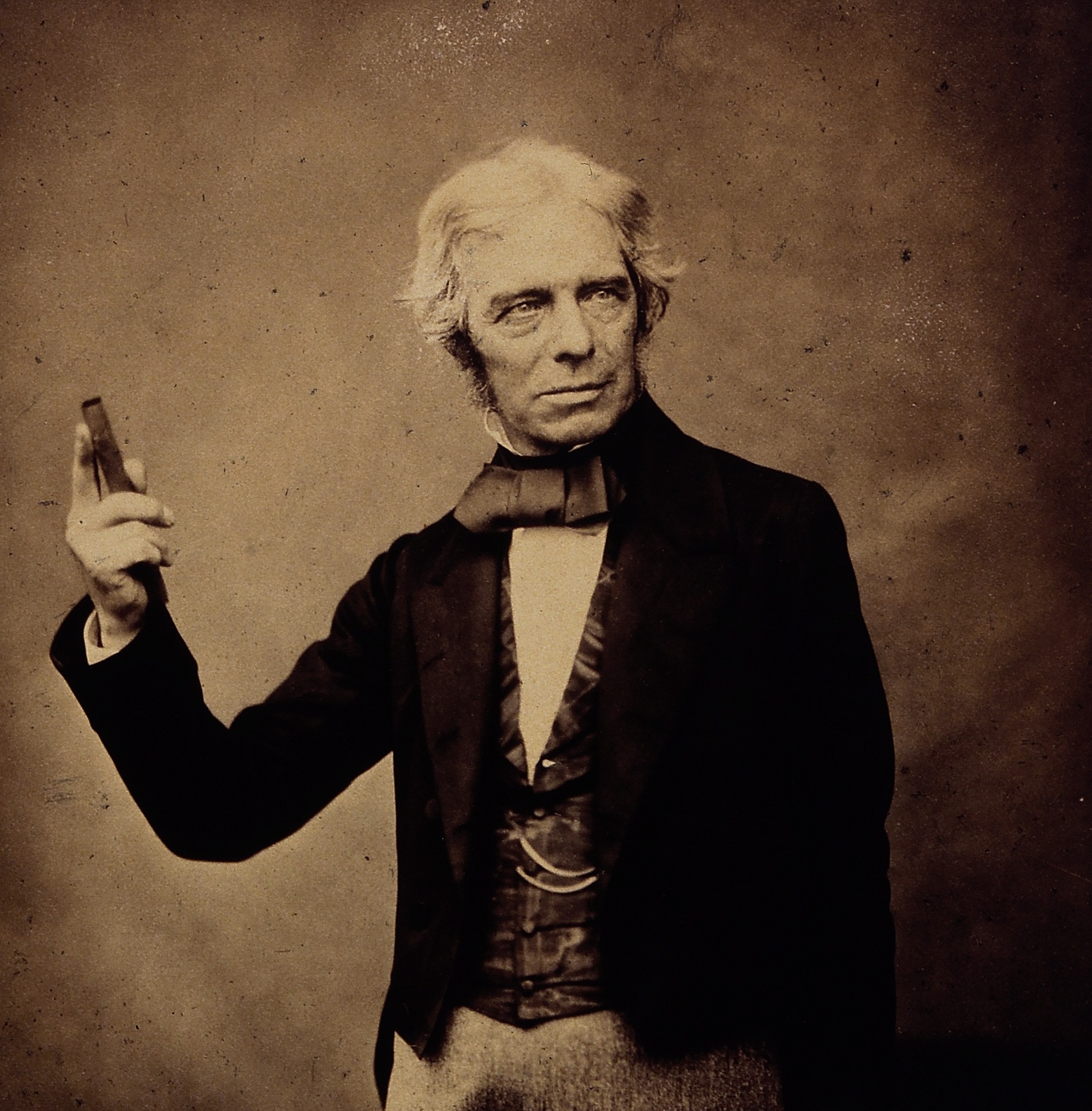

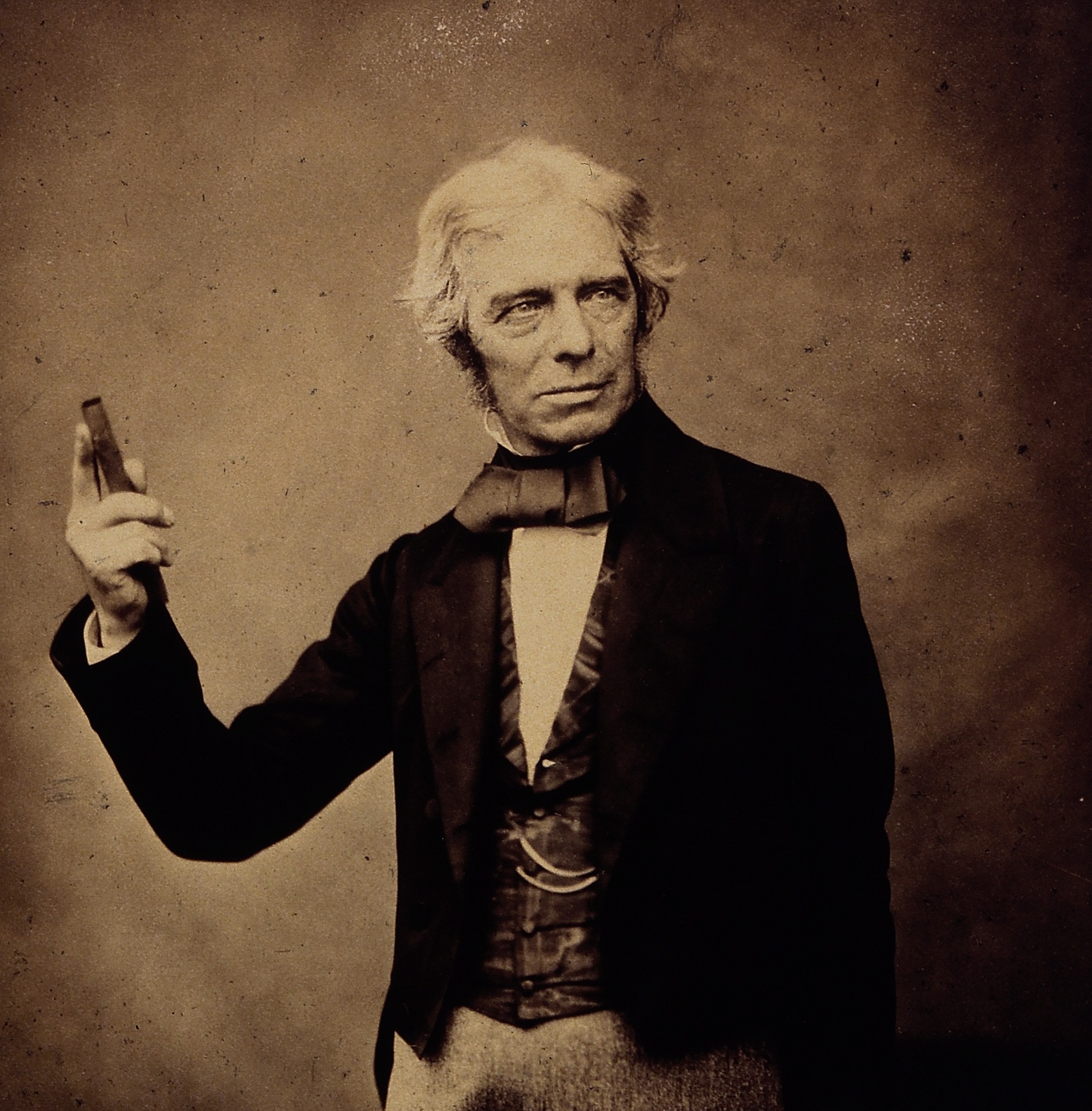

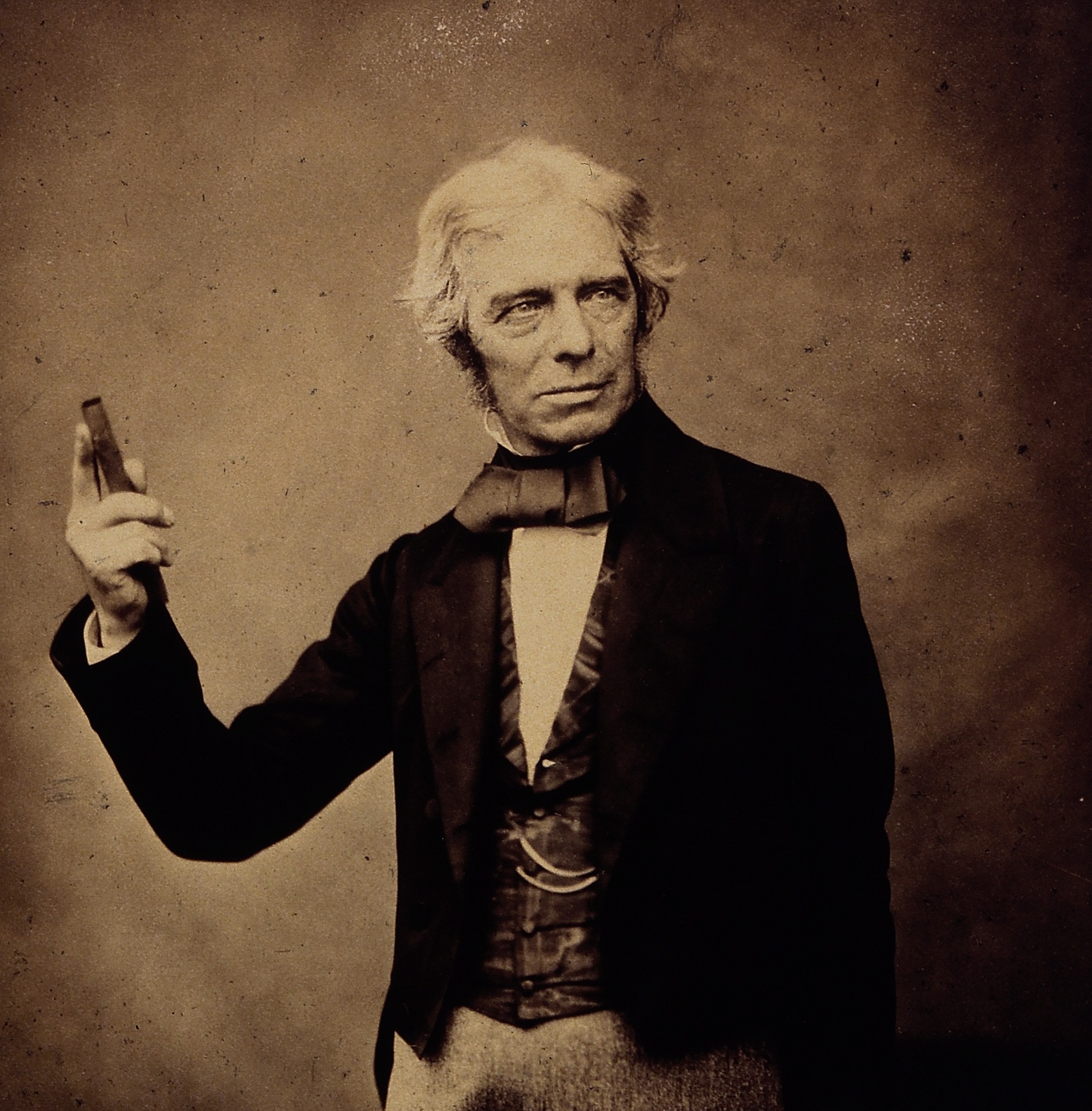

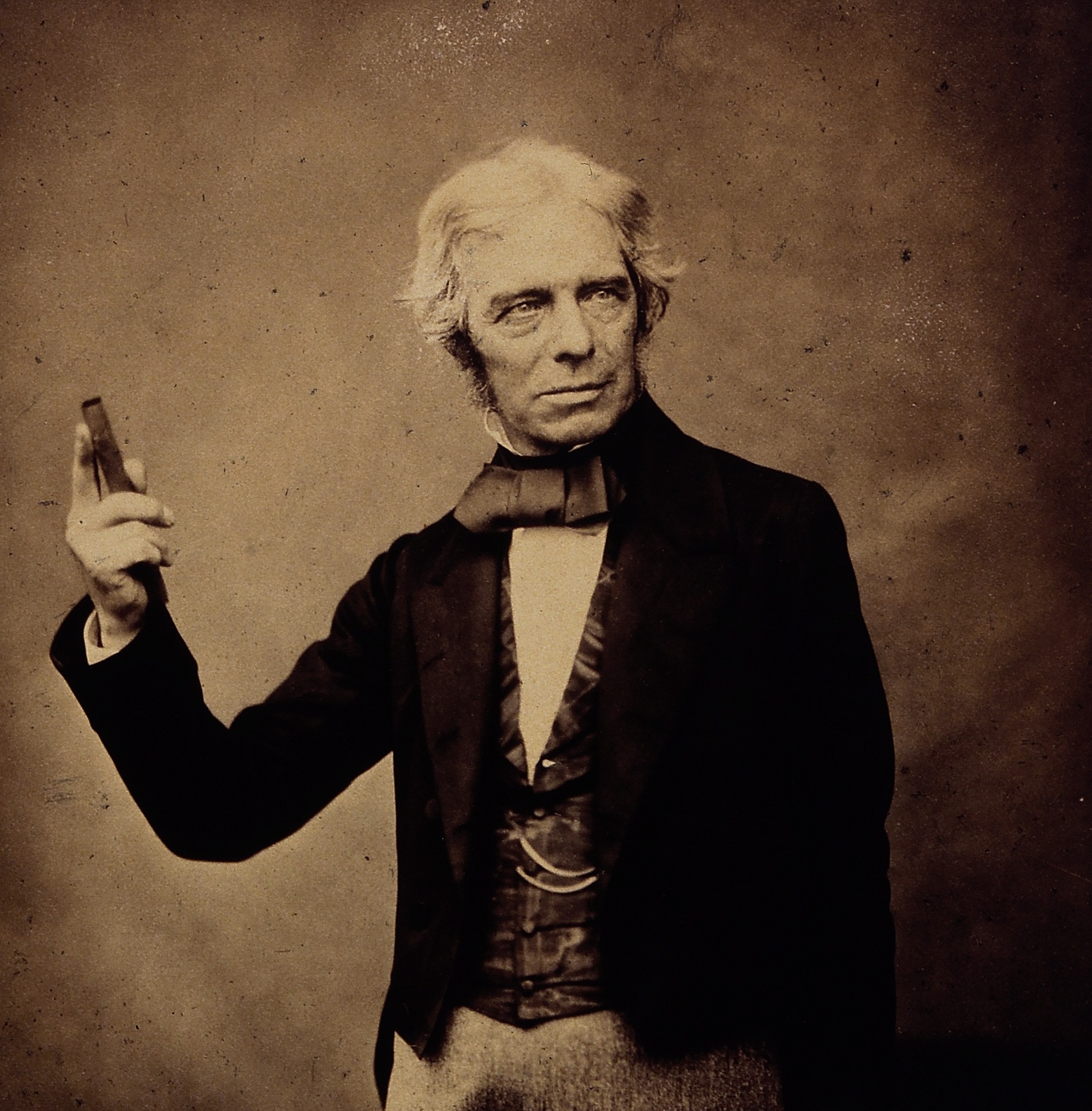

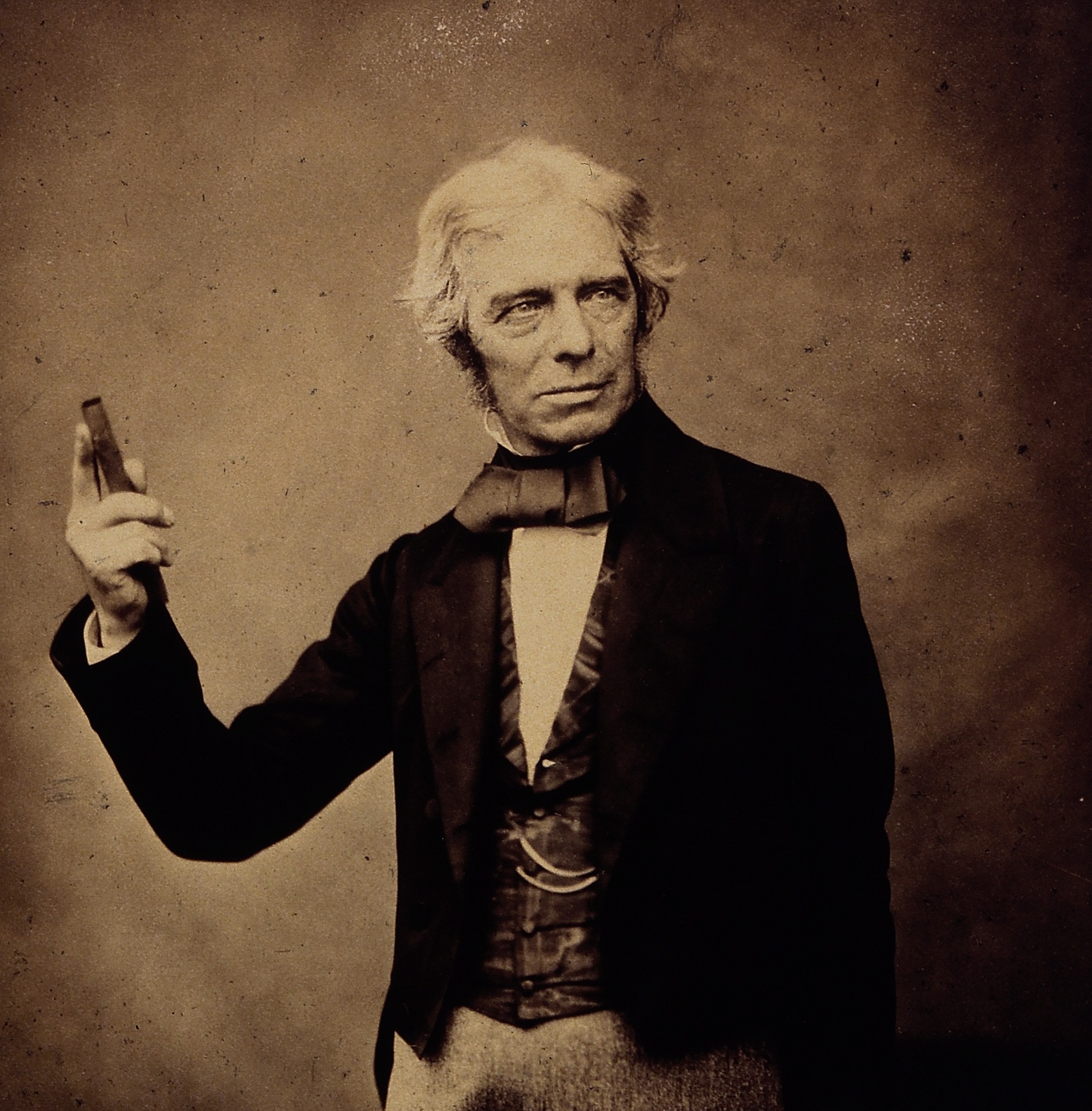

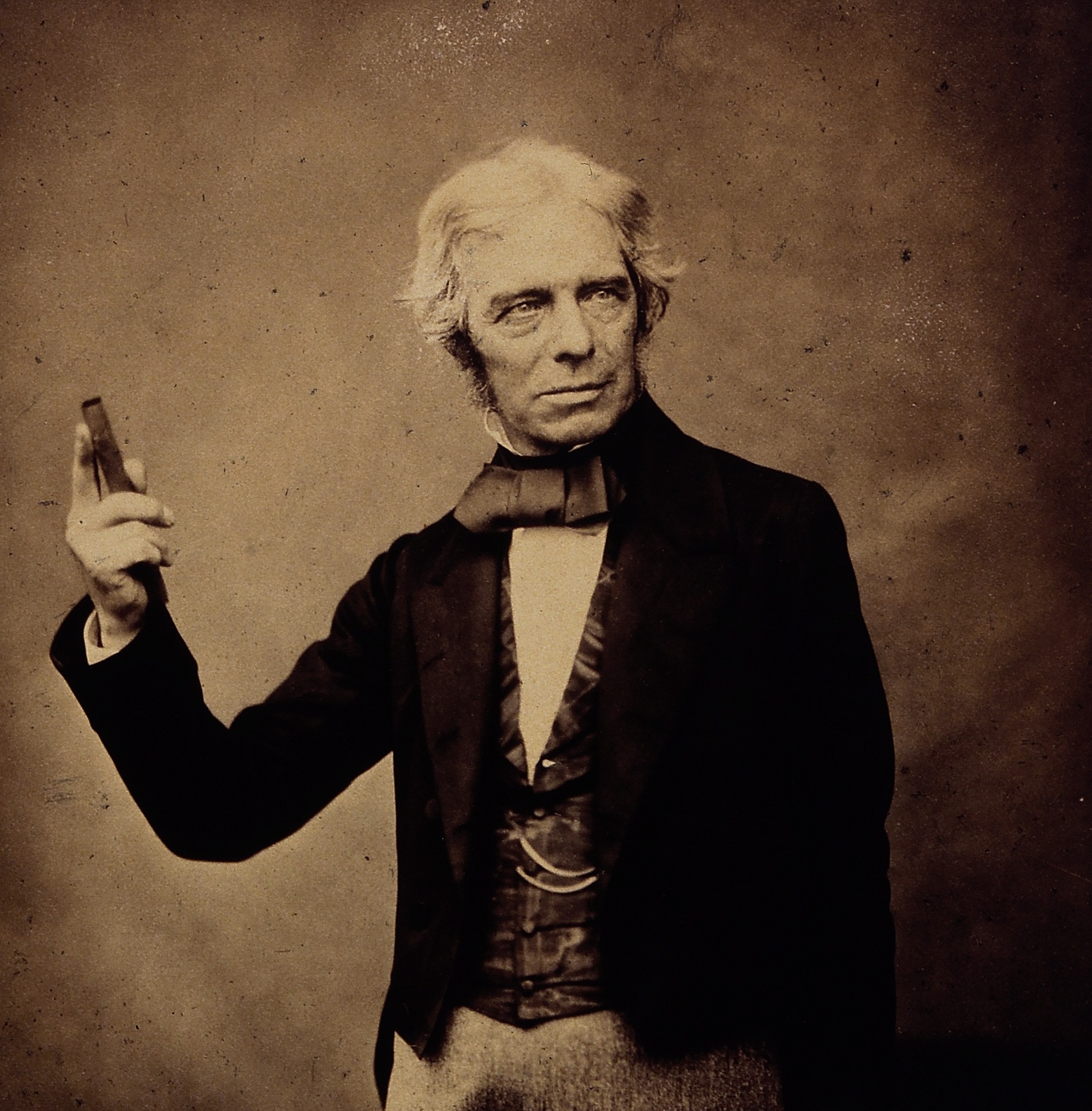

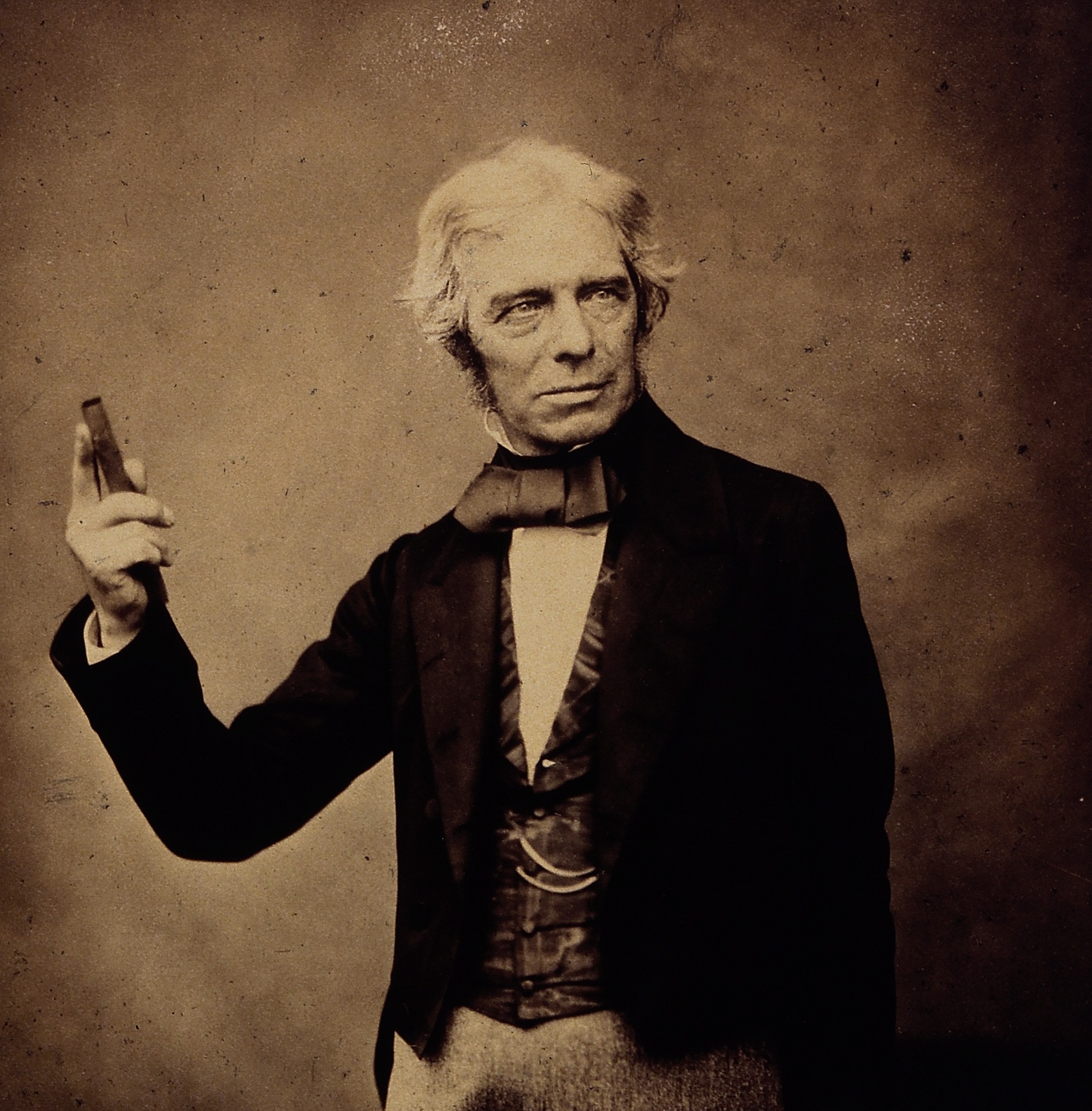

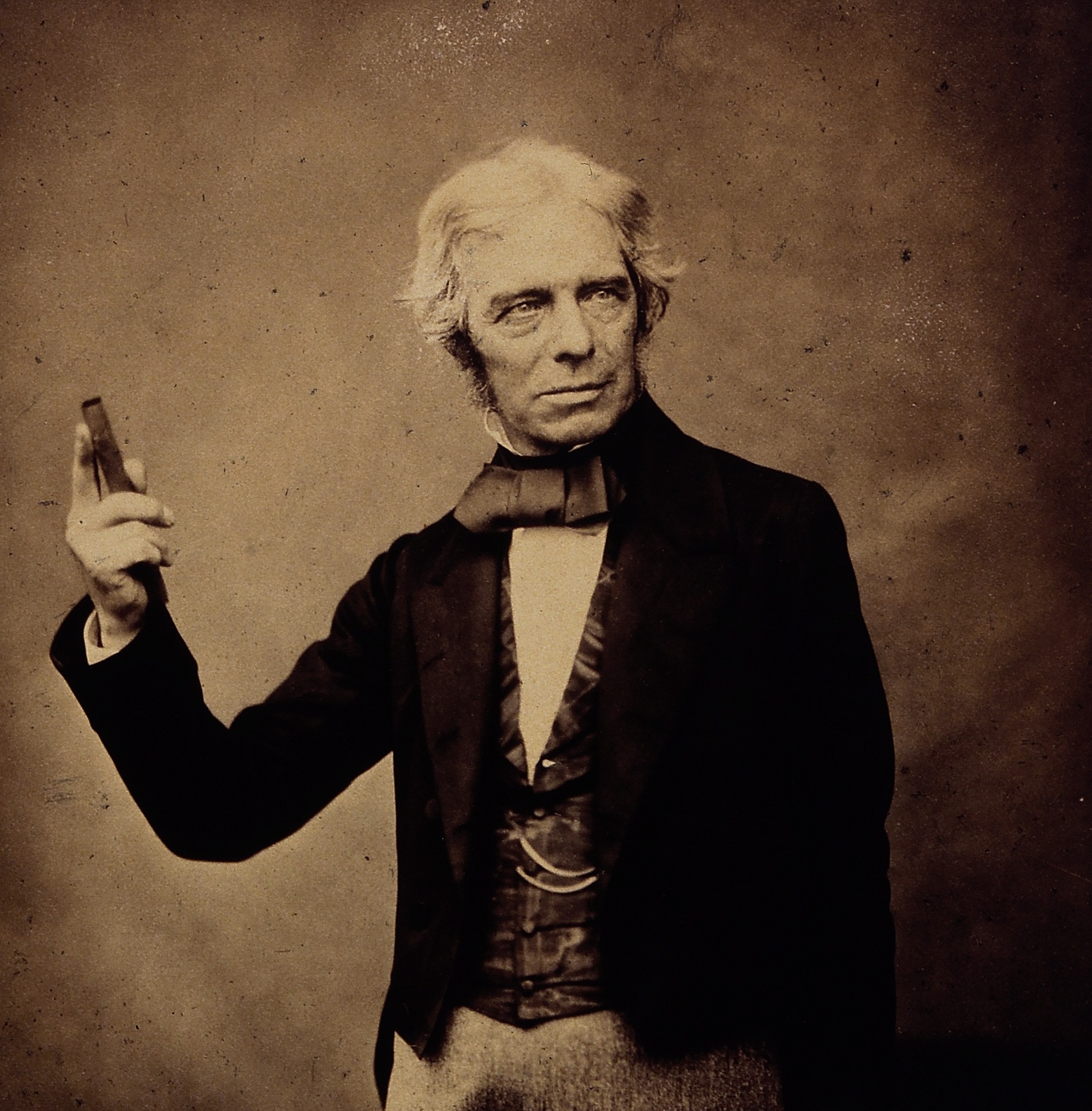

What is the secret of their success? A lot of the credit has to go to their creator, Michael Faraday, who, as well as making world-changing scientific discoveries, was arguably Britain’s greatest science communicator. In this, he was a product of the Royal Institution, which was founded in 1799 as a place not for doing science, but for giving talks about it.

When, in 1813, the organisation hired the 21-year-old son of a blacksmith, it created the most ironic circumstance in the history of science. Here was the pioneer who would uncover the principles of electromagnetism, employed as a humble assistant to lecturers in the Royal Institution’s theatre. It’s as if Shakespeare had started his career as a stagehand.

Yet from his vantage point in the shadows, preparing the tapers and the test-tubes that eminent lecturers would use in their talks, Faraday analysed the challenges of public speaking. His rigorous mind instinctively searched for its deeper principles, and a few months later, he wrote a letter to a friend, sharing rules that still hold true today.

Rule 1. Keep it brief. “I disapprove of long lectures,” remarked the young apprentice. “One hour is long enough for anyone, nor should they be allowed far to exceed that time.”

Rule 2. Keep it engaging. Don’t on any account turn your back on your listeners, Faraday counselled. But instead, focus all your powers on their “pleasure and instruction”.

Rule 3. Keep it spontaneous. Write out your talk if you must, Faraday said. But refer to it only occasionally, without “confining your (undefined) tongue to the exact path there delineated”.

With care and effort, he suggested, you have a chance of gripping your listeners’ attention from start to finish. Or as he put it in his letter, “A flame should be lighted at the commencement and kept alive with unremitting splendour to the end.” He was to remember these rules when, at around this time of year in 1825 (the exact date of the innovation has been lost), Faraday inaugurated the Royal Institution’s Friday Evening Discourses.

Spontaneous, engaging, and (at least by the standards of the time) brief, these one-hour talks proved a smash hit—so much so, in fact, that they saved the finances of the organisation. “The Royal Institution was then on the brink of collapse owing to a nationwide economic crisis,” explains Frank James, Professor of History of Science at UCL. “Faraday knew that the only way of saving it was to increase membership. But in order to increase membership, he had to offer something in return. What he offered was the Friday Evening Discourses.”

For years, Faraday gave the lion’s share of the talks himself. Later, they were delivered by some of the greatest minds in science from across Britain and further afield: pioneers such as the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, who developed the periodic table of elements, and Cambridge’s J.J. Thomson, who used a Discourse to announce his discovery of the electron.

For a sense of the prestige the Discourses accumulated, consider a few milestones in the history of photography, all of which were marked on a Friday Evening in the theatre of the Royal Institution. The invention of black and white photography was first announced at a Discourse in 1839. It was at a Discourse in 1861 that the public had its first glimpse of a colour photograph: a study of a tartan ribbon. And how about the moving picture? That was first revealed, in rudimentary form, to the British public at a Discourse in 1882. Using the rotating disc of his zoopraxiscope, the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge displayed an animation of a galloping horse to an audience that included the Prince of Wales.

Or take the first time that recorded sound was ever demonstrated in Britain. That was at a Discourse, too. In 1878, in the Royal Institution’s theatre, the engineer William Preece recited the first words of the nursery rhyme Hey Diddle Diddle into a phonograph, which registered the sounds as indentations in a sheet of tinfoil, and played them back in a creaky voice. Then the Royal Institution professor John Tyndall stepped forward and delivered a snatch of Alfred Tennyson’s great poem Maud The phonograph mimicked it, to the amazement of the listeners, not least Tennyson himself, who was in the audience.

A milestone in itself, that Discourse also embodies the core lesson of the world’s greatest science talks: namely, that the very best communicators, who deserve to be ranked up there with Faraday, find a way to speak at two registers. Like the phonograph reciting a children’s ditty first, then an adult poem, they engage informed and less informed listeners. Pixar does this with films such as Toy Story and Up, which appeal to adults as much as children. You can see it, too, in the prose style of The Week magazine, where I used to work, which engages those in the know, but also makes sense to readers who are totally ignorant of the subject in question. But the Royal Institution got there first with their talks in the 19th century.

The two-registers challenge was one that Huxley was painfully aware of when he delivered his Discourse. As he wrote to his wife, what he found most daunting was the mixture in the audience, which contained both “the first scientific men” and “fashionable ladies”. This explains his sense of terror, for how on earth was he supposed to please both audiences?

This conundrum is, I think, at the heart of the fear of public speaking, which is reportedly the most common phobia—more widespread than the fear of spiders, or heights, or death. We’re all fairly familiar with the challenge of speaking one-on-one, or to a group of colleagues we can assume will know a bit about our subject. But when an event is open to the public, and draws an audience of 25, or 100, or the 400 that file into the Royal Institution’s theatre, we cannot make that assumption. Pitch it too low and you’ll engage the punters but fail to impress your rivals. Pitch it too high and you risk sending the punters into a coma.

When I ask my colleague, the physicist Prof. Yang-Hui He, he tells me there is more than one way to skin a cat. “You can keep switching between registers, throwing in something for the scientists and something for everyone else. Or you can do what I did, when I gave my Discourse in 2023, which is to start simple, and slowly make it more intricate as you go along.”

Where Yang, who is the best natural speaker I know, most agrees with Faraday is that you should on no account read out your talk in full. “People write out their speech because they feel nervous and they think writing it out will make them feel less nervous. But the irony is that it has the opposite effect. When they come to read it out, it sounds stiff and awkward. And they hear that and it makes them even more nervous. And then they lose their place and get in a muddle and everything goes to hell. You just have to talk, like I’m talking now.”

Easier to say than to do, but this sounds right. And I would add, from my own experience, that there’s a kind of magic in extemporisation. Read a story to a child and they enjoy it. But make it up as you go along and they are mesmerised. In its purest form, this is the real-time spectacle of thought. So although some things are lost when you diverge from the page—you might leave out some points you intended to make—the wins outweigh the losses.

Of course, for anyone familiar with the clammy hands and sledgehammer heartbeat of stage fright, there are other treatments. According to Frank James, who for many years was in charge of the Royal Institution’s Discourses, some speakers have soothed their nerves with alcohol. But it’s a slippery slope, he warns. There was one distinguished physicist, for instance, who drank three large glasses of white wine before his talk—and “you could tell”. Thereafter, Prof. James ensured that speakers were always confined to a single glass of wine beforehand. Once they had spoken, of course, “they could do whatever they wanted”.

Did Faraday himself ever suffer from nerves? It’s hard to know, but we can be sure he wouldn’t have treated them with wine. As an adherent of Sandemanianism, a strict form of Protestantism, the great man didn’t drink. There is evidence, at least, that he took few chances. “Faraday continually worked to become a better lecturer,” says Katy Duncan, a postdoc in the history of science at the Royal Institution. “He attended evening classes and paid for elocution lessons. He also made his teacher attend his lectures and give him critical feedback.” The result was that “the audience may have had the impression of a natural and free-flowing lecture, but it was the result of careful curation and practice”. Until late in his life, Duncan tells me, he kept at it: rehearsing and refining his skills as a public speaker.

In this respect, he incarnated the spirit of the Royal Institution, which remains a world leader in science communication. Above all in its Friday Evening Discourses, you can learn about cutting-edge science, while enjoying masterclasses in the art of speaking at two registers. This is in evidence, for example, in my friend Yang’s Discourse on how geometry shaped modern physics, and in the Discourse given a few weeks ago by Nobel winner Prof. Geoffrey Hinton about what AI is learning from biological intelligence. You can find these, and many other recent Discourses, for free on the Royal Institution’s YouTube channel.

Or if you want to experience a one-hour Discourse in the flesh, go to rigb.org/whats-on and book yourself a ticket for a mere £20. When you make it to the theatre, remember to tip your hat to the 200th birthday of the world’s greatest science talks. Spare a thought, too, for the speaker, who may be grappling, like their predecessors, with the two-registers challenge.

If they are, and assuming that they overcome it, they will be rewarded afterwards with a sense of relief in proportion to the fear they suffered before. That, at any rate, was the experience of Thomas Huxley, who said of his Discourse in 1852 that he took a “profound subject” and played “battle and shuttle-cock with it” in order to please everyone present. The result was a roaring success, which had the effect of banishing Huxley’s nerves for good. “After the Royal Institution,” he wrote, “there is no audience I shall ever fear.”

Thomas Hodgkinson is a science writer at the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences.